The profession of window cleaning is the result of a synergistic relationship between two separate innovations of human civilization: Glass making and building construction. Both of which are the product of rich, long histories in their own right. To provide the context for this article, extremely brief overviews are given to set the stage and are by no mean intended to be complete.

The profession of window cleaning is the result of a synergistic relationship between two separate innovations of human civilization: Glass making and building construction. Both of which are the product of rich, long histories in their own right. To provide the context for this article, extremely brief overviews are given to set the stage and are by no mean intended to be complete.

Ancient origins

Glass has long been a material used in human culture. Deep mysteries surround exactly which ancient culture became the first to combine sand, soda-line and ashes in high temperature to become glass. The ancient Roman historian Pliny suggested that Phoenician merchants first made glass in the region of Syria around 5000 BC. Archaeological evidence indicates the first man-made glass originated in Mesopotamia around 3500BC, although glass-making origins are also demonstrated in Egypt around the same period and is likely a result of the trading network between the two cultures.

The collapse of the Roman empire saw a decline in glass manufacturing techniques which did not really pick up again until the 13th century. The type of glass we see every day in windows and storefronts is called sheet glass and on March 25, 1902, Irving W Colburn patented the sheet glass drawing machine, making the mass production of glass for windows possible.

The first building to feature a glass curtain wall was Oriel Chambers in Liverpool, built in 1864, it was framed in iron and was five storeys tall. This innovation led to further developments, shifting away from load bearing masonry to a steel skeleton which supports the weight of the structure. The Home Insurance Building in Chicago at 138 ft and ten storeys was built in 1885 and is the world’s first skyscraper to use this technology. Less than fifty years later, the tallest building in the world, The Empire State Building was a stunning 1250 feet, 102 storeys with and has 6514 windows.

The first building to feature a glass curtain wall was Oriel Chambers in Liverpool, built in 1864, it was framed in iron and was five storeys tall. This innovation led to further developments, shifting away from load bearing masonry to a steel skeleton which supports the weight of the structure. The Home Insurance Building in Chicago at 138 ft and ten storeys was built in 1885 and is the world’s first skyscraper to use this technology. Less than fifty years later, the tallest building in the world, The Empire State Building was a stunning 1250 feet, 102 storeys with and has 6514 windows.

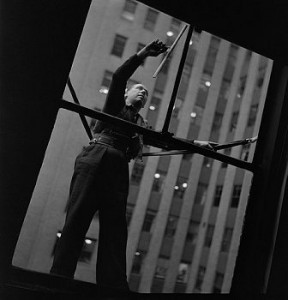

Workers of the trade are often by necessity required to be trouble shooters and innovators in their own right. As buildings continued to get taller, The challenge of safely cleaning the windows became an issue. Lugs or eye bolts were embedded in the building on each side of a window, cleaners then wore a belt similar to those used by electrical linemen and would climb out of the window and attach each end of the belt to the hooks. The window cleaner would lean back against the belt with his toes on ledges only a few inches wide and clean the window. Incredibly labour intensive and requiring large crews to complete the work, this method was quickly abandoned as rope descent systems began to appear.

Although abseiling, a technique used by mountain climbers dates back to 1876, the use and promotion of descenders for window cleaning was a by-product of the Vietnam War. Using a combination of ropes and descending equipment, a platoon could quickly and safely exit a helicopter to reach the ground below. Vets returning from Vietnam who used these systems adapted them to the window cleaning industry.

Just as advancements in technology allowed for more efficient glass production and building construction, working from heights continues to get safer as well. Innovations in the industry including the bosun’s chair, descent & ascent systems, parapet clamps, swing stages, aerial lifts and water-fed poles contribute to a safer work environment. Also, regulatory bodies such as WCB develop safe work standards and oversee the industry while industry specific societies such as SPRAT provide recognized training and accreditation.

The origin of the squeegee dates back to the middle ages as a tool made of wood called a “squilgee” was used by fishermen to scrape fish guts from the boat decks. The first modern squeegee, the “Chicago Squeegee” was a heavy and cumbersome tool that featured two stiff blades fastened with 12 screws to hold it all together. This design was further improved by Italian immigrant Ettore Steccone who invented a lightweight, brass tool with a single, flexible rubber blade dubbed “The New Deal”. This design is so efficient that it has remained basically unchanged since its inception in 1936.

Not just a window cleaning tool, the brass-handled Ettore squeegee saved the lives of five men trapped in an elevator during the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001. Quick thinking window washer Jan Demczur pried open the elevator doors and used his squeegee to cut through the drywall of an elevator shaft stuck on the 50th floor, fleeing from the building five minutes before it came to the ground.

One of the more recent innovations is the telescopic,water-fed pole which allows the worker to safely clean windows up to 60 feet in height from the ground. This system is ideal for low-rise buildings which typically do not feature roof anchor systems. Advancements in technology such as carbon-fibre and water-purification systems enhance the output of this tool, making it a formidable addition to the window cleaners toolkit.

One of the more recent innovations is the telescopic,water-fed pole which allows the worker to safely clean windows up to 60 feet in height from the ground. This system is ideal for low-rise buildings which typically do not feature roof anchor systems. Advancements in technology such as carbon-fibre and water-purification systems enhance the output of this tool, making it a formidable addition to the window cleaners toolkit.

Another product emerging on the market are automatic window washing systems. Working similar to a robotic vacuum, these systems travel up and down the side of a building. An interesting idea, these devices seem to be limited in capacity to buildings with minimal architectural features, and have a long way to go before replacing their human counterparts.

What does the future of window cleaning look like?

The window cleaning industry has firm roots in problem solving and troubleshooting. Even to this day with all the advances in technology and engineering, window cleaning is still at times an afterthought, a problem left to the professionals of the trade to figure out. It is this environment that fosters the high level of ingenuity responsible for innovations in the industry. Consider the tallest building in the world, Burj Khalifa. Completed in 2010, standing 2723 feet in height, it features 24,348 windows totalling 1.3 million square feet of glass! It is an understatement to say that Burj Kalifa represents the state-of-the-art in building design.

Access for the tower’s exterior is provided by 18 permanently installed track and fixed telescopic maintenance units weighing up to 13 tons each. The units are stored in garages within the structure and are not visible when not in use. Manned by a 36 person crew who wear protective clothing resembling moon suits to shield them from the intense heat which can reach in excess of 50˚C these daring cleaners still use traditional soap and squeegees to carry out their work.

Already plans are underway for a tower that will put Burj Khalifa in its shadow. With a planned minimum height of 3280 feet, the Kingdom tower will be about 50 storeys taller than its rival. As human ingenuity and innovation continue to push the boundaries of architecture to new heights, so too does the window cleaner meet the challenge of an ever evolving profession.